Colonialism (cont.) Derivatives of the word ”colony” have been prominent in this month’s commentary, most notably ”decolonization.”

I gave the subject of colonialism a good workover back in my March Diary: the segments headed ”Gilley on colonialism” and ”Reason and authority.”

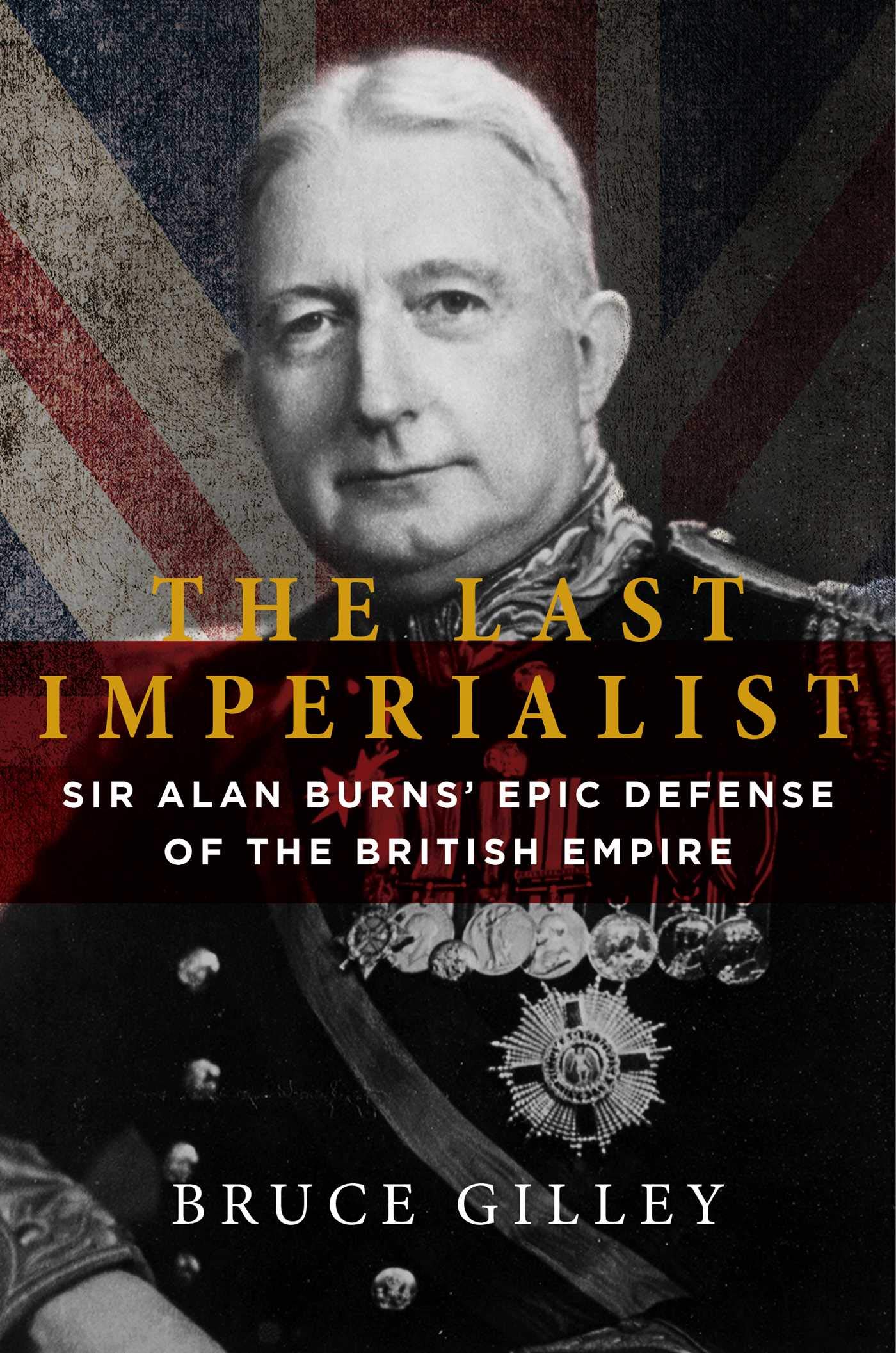

The Gilley in that first segment heading is Bruce Gilley, Professor of Political Science at Portland State University, whose 2017 article ”The Case for Colonialism” caused a fuss at the time.

The second of those two March segments was inspired by my having read Prof. Gilley’s 2021 book The Last Imperialist: Sir Alan Burns’s Epic Defense of the British Empire. My diary comments included the following:

The second of those two March segments was inspired by my having read Prof. Gilley’s 2021 book The Last Imperialist: Sir Alan Burns’s Epic Defense of the British Empire. My diary comments included the following:

Bruce Gilley is not alone in pushing for a re-evaluation of colonialism, at least in the ”Northwest/Germanic” European variety. My March 4th copy of The Economist carries a review of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning by British theologian Nigel Biggar. Title of the review: Nigel Biggar tries—and fails—to rehabilitate the British Empire. Subtitle: ”Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning relies on hoary arguments and selective evidence.”As you can tell, and as you’d expect from a leading organ of globalist orthodoxy, The Economist’s review disapproves of Biggar’s pro-colonialist approach.

In a footnote to that segment I noted that the ”Letters” in the April 1st issue of The Economist led off with push-back from Nigel Biggar against the March 4th review.

All the October buzz about ”decolonization” in relation to Israel and Palestine, along with some reading this month that I shall get to shortly, has left me feeling that those two March segments were incomplete. In what follows here I shall try to complete them.

In which I am a victim of racial discrimination. In the first of those March segments about colonialism I played the card I usually play when the subject comes up: My experience of living under actual colonialism in the British colony of Hong Kong, 1971-73.

A good number of the Hong Kong Chinese I had gotten to know were refugees from Communist China. Some had fled from the great Mao famine of 1959-61, others from the disorders and persecutions of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s. One of that second group, a cheerful young fellow in my night-school English class, had swum four or five miles across open sea from the mainland, braving sharks and trigger-happy ChiCom coastguard boats to get to the colony.It was natural for a thoughtful young person of vaguely Leftist opinions—i.e., me in 1971—to wonder why, if white colonialism was so awful and nonwhite self-government such a blessing, so many people would risk life and limb to escape to the former from the latter.

My opinion of colonialism began evolving just about there.

I didn’t write in March (and I don’t think I have ever written) about a curious experience I had in those Hong Kong years: an experience of flagrant racial discrimination with myself as the victim.

Here you need to know that Hong Kongers of all ethnicities and backgrounds, when speaking English, refer to white people in the colony as ”expats.” (In Cantonese, the majority language of the place, the commonest terms were gwái lóu and gwái tàuh, literally ”ghost guy” and ”ghost head.”)

Back in England before going to the Far East I had worked for two years as a computer programmer on the big old mainframes that were then state of the art (64K of main memory!). To support myself in Hong Kong I taught English at first. After a while, though, I figured I could do better as a programmer. Hearing from a friend that a certain big company was hiring, I put on my best jacket, headed to their main office, and asked if I might speak to the IT manager.

As usual with walk-in applicants, they kept me waiting for a while in a spare office room. At last, though, the door opened and a smart young Chinese lady came in. I stood, gave her my best smile, introduced myself, and asked about job opportunities for experienced programmers.

She replied, in excellent English: ”I’m sorry, we don’t hire expats.” End of interview.

Reparations!

Globalism on colonialism. Here’s a little plagiarism—as a public service, of course.

The Economist online version lives behind a paywall. As a subscriber, I can hop lightly over that paywall. I hope the gents at The Economist won’t mind my doing so. Been subscribing for decades, guys.

The Economist online version lives behind a paywall. As a subscriber, I can hop lightly over that paywall. I hope the gents at The Economist won’t mind my doing so. Been subscribing for decades, guys.

Here then are, first, the magazine’s March 4th review of Nigel Biggar’s Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, then Prof. Biggar’s letter.

• The review:

Nigel Biggar tries—and fails—to rehabilitate the British Empire”Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning” relies on hoary arguments and selective evidence. For a professor of theology, Nigel Biggar has a sharp appetite for controversy. One of his previous books defended the concept of the “just war”. In 2017 he set up a research project on “Ethics and Empire” at the University of Oxford. He was denounced for suggesting that it might be intellectually credible to re-evaluate the morals of the British Empire. To his critics, this did not sound like serious history. His latest book is an effort to set them straight.

True to form, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning takes aim at the verities of the left-leaning academic establishment—in particular the modish academic discipline of post-colonial studies. The book is determinedly revisionist and provocative, often foolhardy and sometimes just banal.

Plenty of people in Britain’s former colonies have long regarded the British Empire as racist and exploitative, even genocidal. What troubles Professor Biggar is that among British historians, too, it is now axiomatic to see the empire as a means to enslave and immiserate other peoples for the benefit of a small white elite. At times, and in places, he concedes, the empire was indeed some, if not all, of these things. But so were most empires throughout history. Unlike most others, he contends, British imperialists were often motivated by a strong sense of ”Christian humanitarianism”: a willingness to use their power and wealth to do good, even if that was not in their own interests.

This is a hoary way for Britons to fend off post-imperial guilt: however reprehensible they were, many told themselves for decades, someone else was worse. Self-serving as it seems, Professor Biggar wants to recover this sense of moral superiority. In that way, he writes, the empire can give those ”who identify ourselves with Britain cause for lament and shame,” but also ”cause for admiration and pride.”

Those last words will make many readers shudder. But the case must be made, the author insists, because only by taking pride in the ”liberal, humanitarian principles and endeavours of the colonial past” can the British, along with Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders, remain confident in their roles as ”important pillars of the liberal international order.”

That is another startling claim—not least in assuming that a liberal international order still exists, and that Britain is a pillar of it. The historical evidence that underpins the argument is shoddy.

Somewhat astonishingly, exhibit A in Professor Biggar’s defence of the empire is the slave trade. He knows Britain was heavily involved in this world-historical evil (as were their fellow Europeans, west Africans and others). But the British, he says, also resolved to abolish the trade, and subsequently the institution of slavery itself. Recent historians have rightly focused on the role of slave rebellions in bringing about abolition in the Caribbean. Here Professor Biggar wants to rewind the clock and re-emphasise the input of white abolitionists, such as Thomas Clarkson, a devout British campaigner.

Most of these activists, he writes, were guided not by a sense that slavery had become uneconomical, but by moral outrage. In the late 18th century they were backed by an early boycott of a consumer product, namely sugar. After emancipation, Professor Biggar continues, Britain invested heavily in the suppression of the slave trade around the world (while paying a fortune in compensation to British former slave-owners). In some analyses, this effort reflected a wish to stop slaveholding economies undercutting British exporters, who now relied on free labour. The author disregards that motive. “For the second half of [the empire’s] life,” he trumpets, “anti-slavery, not slavery, was at the heart of imperial policy.”

Ranging more widely, he takes on the common charge that the British were slow to introduce democracy and other civil rights in their overseas territories. In reality, he thinks, the pace of progress rarely lagged far behind that in Britain itself, as in the gradual extension of the franchise there. The survival of the empire, he argues, rested largely on the co-operation of millions of Indians, Africans and others. He does not dwell on the often divisive patronage that helped secure this acquiescence, nor on the fundamental lack of choice that citizens of the colonies faced, both of which were underpinned by force.

As for the widespread bloodshed and repression: with the tone of a dogged barrister, Professor Biggar tackles some of the most notorious incidents in a bid to show that, even at its worst, the empire was not “wantonly violent”. For instance, he argues that the sacking in 1897 of Benin City in present-day Nigeria was in part justified by a desire to end slavery and human sacrifice there. In this account, the killing and looting that ensued were collateral damage.

These points often rely on a naive distinction between purportedly high-minded policymakers in Whitehall and the assorted settlers, adventurers and soldiers who (to take one example) shot people in India from cannons to discourage rebellion. To those on the receiving end of such brutality, it mattered little that some board of inquiry in London might later tut-tut—as happened in the case of the Amritsar massacre of 1919 (pictured), in which 379 peaceful Indians were killed by a trigger-happy British unit and hundreds more were wounded.

”Pictured” refers to the image at the top of the Economist page of someone staring at a painting of the massacre.

His new book, “Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning”, is determinedly revisionist and provocative, often foolhardy and sometimes just banal https://t.co/IZMPsxbVUO

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) March 13, 2023

The claim that the Amritsar mob—armed with bludgeons and outnumbering the 50 rifle-armed troops by up to 200-1—were ”peaceful Indians” is denied by, among others, Paul Johnson in Modern Times. The Economist says ”a trigger-happy British unit” rather than ” trigger-happy British troops” because the units defending Amritsar were the 9th Gurkha Rifles and 59th Scinde Rifles—i.e., native troops.

Professor Biggar seems unfazed by this cruelty and bloodlust, observing that ”any long-standing state” harbours ”evils and injustices.” This is a lazy and banal defence, especially since he reckons this particular empire had higher moral standards than others. He also asks readers to believe the empire was not ”essentially racist.” Yet the entire edifice of colonial rule, from exclusive all-white men’s clubs in imperial outposts, to the operation of justice and the courts, was founded on the alleged superiority of educated white men.

And as for the claim that liberal internationalism grew out of what the empire got right: for what it is worth, that creed owes much more to intellectual traditions and luminaries, such as George Orwell, that were opposed to imperialism, than it does to those who thought the empire could be a force for good. In a spirit of open inquiry, it is fair to question contemporary orthodoxy about the British and other empires. But Professor Biggar goes much too far.

• Nigel Biggar’s April 1st letter:

Nigel Biggar respondsYour review of my book, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, judged it to be ”often foolhardy and sometimes just banal” …

First, you tell us that plenty of people ”in Britain’s former colonies have long regarded the British Empire as racist and exploitative, even genocidal.” Sure, but the subjects of British rule didn’t all think the same thing. For example, Chinua Achebe, the African nationalist man of letters, refused to condemn British colonial rule shortly before he died in 2013.

Next, your review was astonished that exhibit A in my case for the growing humanitarianism of the British Empire is ”the slave trade.” Of course, my prime exhibit is the fact that Britain was among the first states in the world’s history to abolish the trade and slavery itself. You then emphasise the role of slave rebellions in bringing about abolition. I acknowledge that on page 56. But until you can present a cogent argument that the humanitarian revolution in British mores, which gathered steam decades before the 1791 slave-revolt in Saint Domingue (now Haiti), did not play a leading role in securing abolitionist victories in Britain’s Parliament in 1807 and 1833, my case stands.

Correctly, you point out that ”in some analyses” Britain’s subsequent investment in suppressing slavery worldwide was intended to stop slaveholding economies undercutting British exporters, now reliant on free labour. But human actions usually spring from several motives and sometimes genuinely humanitarian motives really do dominate economic ones. You also claim that I argue that the empire was not ”wantonly violent.” That is untrue: I admit it was—sometimes.

Finally, you find ”lazy and banal” my point that the empire was like any long-standing state in harbouring evils and injustices. But that was merely the elementary stage in the larger argument, clearly stated in the Conclusion, which you overlooked. That concludes that the British Empire wasn’t ”essentially” racist and murderous and that it contained growing humanitarian and liberal elements, which found climactic expression when, between May 1940 and June 1941, the empire stood alone (with Greece) as the only military opposition to the massively murderous racist regime in Nazi Berlin.

Ambivalence of the colonized. This month I got around to actually reading Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning.

Not bad; although the title is misleading. The book is not about colonialism in general, only about the British Empire. French, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, German, Italian, Russian, Turkish, American, Japanese, and Chinese colonialism are not covered, nor even—except for a scattering of side references—mentioned.

Prof. Biggar teaches at Oxford University. I guess that explains his Brit-centric approach. For a reactionary like me there’s some comfort in knowing that there are still respectable scholars of that type at the big old universities, still cherishing the view that if Britain didn’t make it happen, it probably wasn’t very important. I bet Prof. Biggar knows to pass the port to the left.

He sure doesn’t skimp on documentation for his arguments. The 297 pages of main text in Colonialism are followed by 131 pages of notes and a 34-page bibliography. Together with the 18-page index, that’s 62 percent text, 38 percent end matter: pretty heroic, even for an academic.

I think he’s given a fair account of his subject, with careful attention to balance in writing about still-contentious matters like the 1940s Bengal Famine. On topics I know well—the First Opium War, for example—his historical judgments are mostly sound.

He will never get general agreement on his ”moral reckoning,” though. The colonized peoples themselves are ambivalent.

Plenty of them, like the friends I made in Hong Kong, prefer liberty, social order, and fairly-administered laws under foreign rule to the insecurity, corruption, and state violence of native despotism or anarchy. Biggar gives examples. Here is a Hausa woman of Nigeria reminiscing about life before colonization:

In the old days if the chief liked the look of your daughter he would take her and put her in his house; you could do nothing about it. Now they don’t do that.

And here is an Englishman in colonial Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) teaching African children in the early 1970s. On one occasion he wrote on the blackboard of his class of black boys a question for discussion: ”Do you think that Rhodesia should have majority rule?” and then waited for a response.

Eventually one boy raised his hand. ”No! I! Do! Not!” he sang out and then sat down.”Why not?”

He … replied, ”Because the tribes will keell each udder” …

”Do you really think that? Or are you just saying that because you think that’s what I want to hear, because I’m a mukiwa [a European]?”

They all laughed, and another boy said, ”We always used to keel each udder before the white man came. The Matabele would come up and steal our cows and keel us, and we had to hide in caves.”

On the other side of the ambivalence is nationalist feeling, as expressed by Lord Byron’s imagined Greek poet, when Greece was still under Ottoman rule in the early 19th century. After referring to one of the rulers of Ancient Greece the poet adds:

A tyrant; but our masters then

Were still, at least, our countrymen.

I suspect that poet’s view is more widely held than you might suppose on merely practical grounds.

Orwell in Burma. Burma hardly gets a mention in Prof. Biggar’s book. That was disappointing, as my previous reading was Finding George Orwell in Burma by American journalist Emma Larkin. Ms. Larkin (it’s a pen name) is a Burma specialist. She speaks the language and has, says the book’s cover blurb, ”been visiting Burma since the mid-1990s.”

I know next to nothing about Burma but I’m an Orwell groupie from far back and couldn’t resist the book’s title when I saw it in the library. It’s an account of a trip the author made there in 2003, with the intention of seeing how much is left of what Orwell knew when he was a colonial policeman there for five years, November 1922 to July 1927.

I know next to nothing about Burma but I’m an Orwell groupie from far back and couldn’t resist the book’s title when I saw it in the library. It’s an account of a trip the author made there in 2003, with the intention of seeing how much is left of what Orwell knew when he was a colonial policeman there for five years, November 1922 to July 1927.

Those five years were Orwell’s raw material for his first novel, Burmese Days, which Emma Larkin describes, not unfairly, as ”rabidly anti-colonial.” He thought the British Empire was just a money racket.

In the course of researching Orwell’s time in Burma, I corresponded with a woman whose father and husband had worked as police officers in Burma in the early half of the twentieth century. She was upset by Orwell’s jaundiced view of colonial society and remembers a very different Burma where relationships between the British and the Burmese were on an equal level. She added that Orwell was unanimously disliked by his contemporary officers because he didn’t fit in and did not seem to enjoy life in Burma—or, for that matter, anything at all.

Whatever the truth about British rule in Burma, the place could hardly have been in worse shape in the 1920s than Ms Larkin found it in 2003, Burma’s 56th year of independence. After some feeble, futile efforts at civilian government, most of those 56 years—and many since—have been spent under military dictatorships of the nastier kind. (There was a spell of comparative liberalization in the 2010s, but a coup in 2021 restored the status quo ante.)

Ms. Larkin in fact develops the conceit that Orwell actually wrote not just one but three books about Burma: Burmese Days of course, but also his dystopia novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. It is true that the stories of the latter two books have nothing to do with Burma; but the totalitarian pictures they draw correspond well, our author says, to life there in the 21st century.

She meets a local named Tha Win Kyi, who used to teach at a government school but was fired for being insufficiently enthusiastic about the regime. Now he makes a living giving private English lessons.

The grand plan, if there is a plan at all, is to abolish the power of thinking, believes Tha Win Kyi. ”Children are not encouraged to question their teachers, and when the teacher asks them a question they dare not answer. It has come to the stage where they see a thing that is not true and they dare not say that it is not true.”

Higher education has likewise been destroyed.

”Now it is almost impossible to fail a university exam in Burma,” said Tha Win Kyi. ”Teachers are afraid of getting into trouble with the authorities if their students are unsuccessful, so they often give them the exam questions in advance.” Students can also bribe poorly paid teachers for higher marks.

All this suppression of thought, speech, and learning is being done against a background of corruption, economic failure, and more or less continuous civil war against and among minority ethnies, with which the country is well-stocked. Burma sounds like a truly awful place. Could colonial rule have been any worse? Hard to believe.

Botanical investigations. The Mrs. and I took a random day off in late October. My lady is a keen gardener and nature-lover. A friend  had advertised the delights of Untermyer Park to her, and she wanted to visit the place as the leaves were beginning to turn.

had advertised the delights of Untermyer Park to her, and she wanted to visit the place as the leaves were beginning to turn.

Untermyer Park is on the east bank of the Hudson River in Yonkers, just north of New York City. For us it is an hour or so’s drive—no great inconvenience. Untermyer was a very successful early-20th-century lawyer who had a mansion and 133-acre estate there, which he left to the public benefit in his will. (He died in 1940.)

The mansion is long gone and the estate reduced to 43 acres. It was desolate for many years, but since 2011 a non-profit, working with the City of Yonkers and supported by state grants, has restored the gardens and structures to beautiful condition.

We strolled around the place happily for three or four hours: Walled Garden, Vista Overlook (i.e., overlooking the Hudson), the Temple of Love (at the top of a l-o-o-ng stairway, causing a certain geezer to grumble: ”Who’s got any energy left for love after climbing all the way up here?”).

Altogether a lovely day out. One peculiar thing that got our attention, though, was a plant that was growing all over in the gardens here. It is a kind of bush; but instead of bearing flowers or fruit, it produces little balloons: an apparently empty sphere of plant tissue two or three inches across. What on earth was the point of the thing?

Mrs. Derbyshire the botanist looked it up on an app she has installed in her smartphone. I don’t have the app, nor even a smartphone, but here is Wikipedia’s description:

Gomphocarpus physocarpus, commonly known as hairy balls, balloonplant, balloon cotton-bush, bishop’s balls, nailhead, or swan plant, is a species of plant in the family Apocynaceae, related to the milkweeds. The plant is native to southeast Africa, but it has been widely naturalized. It is often used as an ornamental plant.

Hey, you learn something every day. ”Bishop’s balls,” huh? I shall explore the etymology of that … when I’ve stopped giggling.

Naming the demon. You slow down as you get older; everybody knows that. I’ve slowed down more than most, though; the sage, select brotherhood (and sisterhood) of people who have followed me for the past quarter-century all know that. They not infrequently email in or ask me in person about it.

It’s true enough, as I am glumly aware. Twenty years ago I could write a couple of editorials and a book review before breakfast and knock out an entire novel in a few weeks, all while holding down a fulltime office job cutting code for a bond brokerage, raising two kids, and doing home improvements on an old property. Nowadays I get up, read my New York Post over breakfast, perform necessary ablutions, walk my dog, check my email, … and it’s time to lie down for a while.

The cause of my lassitude is no mystery. In mid-2011 I was diagnosed with blood cancer; in the first few months of 2012 I underwent chemotherapy.

That sent leukemia into hiding for five years but it left me with chemo brain. I was observably slower than before: less energetic, less engaged, less interested in things. I’d heard about chemo brain and vaguely supposed it was one of those not-really-real mental conditions people believe themselves into for inward reasons. No, it’s real.

In 2017 the leukemia came back. By that time, however, researchers had developed a miracle drug that made chemo unnecessary. I’ve been taking a $360 pill every day since, courtesy of Mrs. Derbyshire’s employee healthcare coverage. God bless those researchers!

In 2017 the leukemia came back. By that time, however, researchers had developed a miracle drug that made chemo unnecessary. I’ve been taking a $360 pill every day since, courtesy of Mrs. Derbyshire’s employee healthcare coverage. God bless those researchers!

I’m still stuck with chemo brain from those 2012 treatments, though. (A further eleven years’ advance into geezerhood likely hasn’t helped any.) That’s tiresome; but it’s become a bit less tiresome since, early this month, a friend introduced me to the formal medical name for chemo brain. The formal name is ”CICI,” for Chemotherapy-Induced Cognitive Impairment.

The friend who introduced me to the term ”CICI” did so by email (he lives in Japan), and I have never heard it used in spoken language. For my own satisfaction I have settled on a pronunciation in the Italian style: chee-chee. That is more fun to pronounce than any alternative I can see, and the frivolity of it cuts the demon down to size somewhat.

Evil portents. Mickey Kaus on Twitter, October 25th.

Latest sign of disorder: Coyotes now roaming freely all over West Side LA—i.e. flat normie grid-streets miles south of the hills that are their home. Howling near Little League fields. Trotting through backyards. I’ve lived here 50 years; never seen this. Must mean something.

I noted on Radio Derb a few months ago the longstanding Chinese folk belief that peculiar happenings in the natural world were portents of great changes in the human sphere. As readers of Fire from the Sun will recall, the word 崩 (pronounced bēng) in old Chinese was used for both a major landslide and the death of an emperor.

Stay alert, citizens!

Sick or sweet? October of course ends with Halloween. Mrs. Derbyshire—37 years resident here, 21 years a citizen, thoroughly Americanized in every other respect—is still baffled by Halloween.

She just doesn’t get it. Making fun with skeletons, shrouds, ghouls and gravestones—say what? There is just something about the festival intractably alien to her. In the Chinese tradition the Angel of Death is an object of fear and loathing, not a theme for games, toys, and parties.

I’m not as creeped out by it all as she is, but it was no part of a mid-20th-century upbringing in my part of Britain. Our autumn celebration was Guy Fawkes Night on November 5th. As I have written:

I’m not as creeped out by it all as she is, but it was no part of a mid-20th-century upbringing in my part of Britain. Our autumn celebration was Guy Fawkes Night on November 5th. As I have written:

We had never heard of Halloween back then. I am told that nowadays, in the glutted abundance of postindustrial society, English kids celebrate both festivals. In fact, Guy Fawkes and his 1605 plot against King James I notwithstanding, they are both the same festival. Fifty years ago, as Iona and Peter Opie noted in their book The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren: ”When darkness closes in on the vigil of All Saints’ Day, Britain has the appearance of a land inhabited by two nations with completely different cultural backgrounds …” Half the nation celebrated Halloween, half held off until Guy Fawkes Night.

We both do our best to enter into the spirit of the thing, though. There’s a bowl of candy by the front door. Baby Michael, our grandson, is not old enough to take trick-or-treating, but he has a dinosaur costume for the occasion.

Happy Halloween, VDARE.com readers!

Math Corner. Did any person of reason and good sense come out of October with a higher opinion of college education in the U.S. than the one he’d held on September 30th? I seriously doubt it. Transcribing those quotes above about Burma’s plans ”to abolish the power of thinking,” in fact, I found myself wondering if some similar scheme is under way here.

It’s not just the humanities that are being enstupidated, either.

San Francisco State University recently put out a help wanted ad for a new math professor.The 1,447-word description includes no information about the specific math skills the scholar will need to do the job.

Nearly the entire post is essentially dedicated to explaining that the position is for someone who knows how to teach math to black and Latino students using equitable and anti-racist methods.

SFSU seeks math professor who uses ’anti-racist teaching strategies’ by Jennifer Kabbany; The College Fix, October 23, 2023

They’re doing this to math? Heaven help us!

Brainteasers. There’s a worked solution to last month’s brainteaser here.

For this month, here’s one that just needs manipulation of elementary trig functions and some basic complex-number arithmetic.

Define SigN to be sin(1) + sin(2) + sin(3) + … + sin(N). The numbers there are all radians, of course.Prove that −1/7 < SigN < 2 for any positive whole number N.

(Credit here belongs, I think, to Sam Walters.)

John Derbyshire [email him] writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him.) He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. He has had two books published by VDARE.com com: FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT (also available in Kindle) and FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT II: ESSAYS 2013.

For years he’s been podcasting at Radio Derb, now available at VDARE.com for no charge. His writings are archived at JohnDerbyshire.com.

Readers who wish to donate (tax deductible) funds specifically earmarked for John Derbyshire’s writings at VDARE.com can do so here.