In fact, invasive foreigners get so many taxpayer-funded freebies that they have enough spare money to send home to the family as remittances. A 2012 article in the Economist called the worldwide flows of remittances a“River of Gold.” Pew Research reported in February that $123,273,000,000 in remittances were sent from the United States in 2012. That’s a stunning amount of money not being spent in the United States, stimulating the American economy. Think about that fact if you are ever tempted to hire a gardener who doesn’t speak English.

A July report from a Chelsea Massachusetts newspaper “Influx Has Everything to Do with Remittance Culture” noted that $2 billion in remittances left the state in 2012 alone, most of it going to Central America.

Remittances are an evil system because the money rewards bad governments: the worse political elites run a country, the more its people leave to seek more money in the first world, from which they often send mini aid checks to families at home.

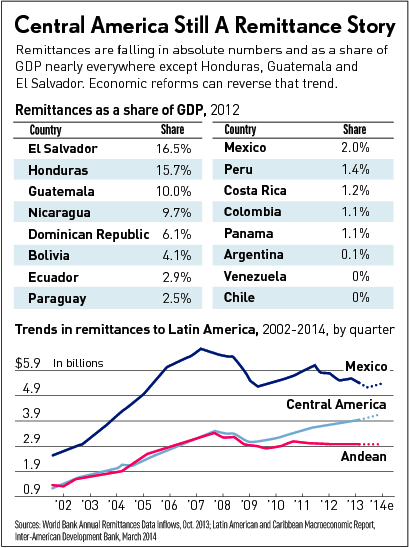

In the corrupt countries of Central America, remittances are a substantial part of the GDP, as shown in the chart above. Moocher Mexico is a wealthy country, consistently #14 in world GDP rankings, and there is no reason why the Centrals can’t do better.

Below, the dollar amount of remittances sent from the United States in 2012 according to the World Bank.

Today’s remittance sob story from the open-borders media centers on a diabetic grandmother in Honduras whose illegal alien grandson sends $100/month for her medicine. The grandson, Jose Luis Zelaya, is now enrolled in a doctorate program at Texas A&M. Where does he get spare money while he is going to school? The Houston Chronicle story omits important details about its star character.

However, the wondrous internet provides more info about illegal alien Zelaya, who turns out to be quite the extrovert. He ran for student body president in 2012 at A&M on a DREAMer platform of diversity, coming in fourth out of six. His PhD field was mentioned as “Urban Education” on the scrounger site GoFundMe.com where he begged for cash for his mother’s surgery.

Below, Zelaya campaigns in 2011 for Texas A&M President (unsuccessfully).

So Zelaya (@JoseLuisInspire on Twitter) has a talent for creative panhandling and promoting himself. You get the feeling his plan is not to acquire an advanced education so he can return to Honduras and help improve it. He has found the diversity gravy train and intends to stay.

Anyway, back to remittances.

How a tide of money fuels a wave of immigration: Cash transfers back home keep families afloat, Houston Chronicle, August 8, 2014Jose Luis Zelaya trekked to a Western Union office inside a Houston Fiesta Food Market last week with one of his family’s regular $100 money transfers. It was for the ailing grandmother who had helped him flee Honduras when he was 13 to find his mother working in Texas.

“She helped me get here,” said Zelaya, an undocumented student who recently was granted a temporary stay in the United States while he pursues a doctorate at Texas A&M University. “It would be inhumane if I didn’t.”

To Zelaya, the money is a small sacrifice for a diabetic grandmother who needs medicine. But it’s an integral part of the complicated tapestry of immigration: As U.S. officials try to stem the flood of illegal immigration from Central America, they are working against a rising but less visible tide of money going back in the other direction.

Immigrants from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador – both legal and illegal – sent home more than $12 billion in remittances in 2013, a record year. Analysts say much of that money went directly to needy family members and loved ones. Inevitably, some also ended up in the pockets of smugglers who guided them north.

Economic realities

In the wake of the recent surge of undocumented families and children in the Rio Grande Valley, the Obama administration says it is working with three Central American nations to improve the desperate social and economic conditions they see as the root of the exodus. Texas Democrat U.S. Rep. Henry Cuellar, who represents the border region around Laredo, says that Central American leaders have told him and a procession of visiting U.S. lawmakers that they “want the kids back.”

But experts on immigration and the global remittance marketplace say policy makers are up against a hard economic reality in their quest to stop the surge. Viewed from Central America, the exodus north is not only a critical source of hard currency; it is also a social “safety valve” for poor nations with little economic opportunity.

“These governments are living off illegal, unsafe and vulnerable migration,” says Inter-American Dialogue researcher Manuel Orozco, a University of Texas-trained political scientist and one of the nation’s leading experts on remittances.

Studies by Orozco and a raft of other scholars show that remittances from relatives who emigrated to the U.S. far outstripped the $237 million in nonmilitary foreign aid that Washington sent in 2013 to Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

Families in Guatemala, for example, received some $5.4 billion in remittances from relatives up north last year, according to the World Bank. In the same year, that nation got $106 million in nonmilitary U.S. aid, according to the State Department.

The remittances also account for a significant part of those countries’ overall economies.

In Honduras, the largest source of unlawful Central Americanimmigrants on the Texas border, wire transfers and other forms of remittance from the U.S. make up almost 16 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, according to World Bank figures. For El Salvador, the figure is 16.5 percent; in Guatemala, remittances are estimated at about 10 percent of GDP.

“The money is the bass fiddle in the background, while somebody is playing the piccolo out front,” said David North of the Center for Immigration Studies. “But it’s very much part of the same orchestra. It’s laying down the beat.”

Texas ranks third

Over the years, immigrants in Texas have been a large part of the remittance economy, ranking third nationally behind their counterparts in California and New York, according to a 2005 Congressional Budget Office study.

In Zelaya’s case, it was his mother, cleaning houses and doing other menial jobs in the Houston area, who paid for the coyote, the human smuggler who helped him on the long journey by freight train to the Rio Grande, which he swam across.

According to recent Border Patrol estimates given to Cuellar, the going $5,000-a-head rate charged by coyotes has produced a $300 million revenue stream just from the approximate 60,000 unaccompanied children apprehended at the border since October.

Given the low-wage economies of nations like Guatemala, where the poor work for less than $2 a day, Cuellar believes much of that money came from remittances from relatives in the U.S. – money that would otherwise be spent in legitimate enterprises back home.

“That’s a lot of money that could have been invested in those countries,” Cuellar said.

The Obama administration and immigration rights advocates stress the humanitarian side of the equation, expressing optimism about improving conditions in Central America with regional cooperation and aid. Some $300 million would be devoted to that effort under Obama’s stymied funding request to Congress.

At the same time, many Republicans in Congress question those countries’ commitment to stopping the flow – of people as well as money.

A move to cut aid

One lawmaker, Friends-wood Republican Randy Weber, is pushing legislation to cut off aid to all three nations – plus Mexico – as a “stopgap” against the influx, which he sees as much as an economic migration as a refugee crisis.

Cuellar argues that expanding legal avenues of immigration, like guest worker programs, would take a bite out of the coyote business. That, in turn, would direct more remittance dollars to the formal economies of Central America, thus reducing the need to emigrate.

But to Weber, the continuing flow of remittances means an ever greater incentive for illegal immigration, and a heightened sense of urgency for tightening the U.S.-Mexico border.

For now, there is no end in sight. After dipping somewhat during the recession, remittances to Central America have rebounded in recent years. Meanwhile, rising violence only adds to economic misery. A national survey Orozco conducted in El Salvador two weeks ago found that 25 percent of poll respondents plan to leave. The top reason given was economic opportunity, he said, followed by crime.

“To a large extent, Central America is a banana economy,” UT political scientist Orozco said. “What it takes is someone to set the tone. Instead, what is being done is silently acknowledging that it pays to have migrants leave who will send money.”

For Zelaya and his grandmother, there seems to be no other choice. “When she gets the money, she tells me ‘you are saving my life.’?”

By the numbers

$12 billion: Amount that immigrants from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador – both legal and illegal – sent home in remittances in 2013, a record year.

16%: Percentage of Honduras’ gross national product that comes from remittances from U.S. immigrants

16.5%: Percentage of El Salvador’s gross national product that comes from remittances from U.S. immigrants

10%: Percentage of Guatemala’s gross national product that comes from remittances from U.S. immigrants

Source: World Bank

Never forget that illegal immigration is all about the money — not freedom or opportunity — just money. When illegals whine that they want a “better life” what they really mean is “more money” which can also take the form of “vanloads” of food stamps, free-to-them deluxe healthcare and subsidized college tuition for the young illegals.

Never forget that illegal immigration is all about the money — not freedom or opportunity — just money. When illegals whine that they want a “better life” what they really mean is “more money” which can also take the form of “vanloads” of food stamps, free-to-them deluxe healthcare and subsidized college tuition for the young illegals.