The only clip I could find was incomplete, but still contains important points about how people in the Rustbelt city of Youngstown are scrambling to earn a living now, although the piece omits the severe economic restructuring that may face us. That part is a scary future without a roadmap, and the TV segment was only five minutes.

The headline here is that America’s most common jobs are likely to be automated: those are driver (cab and truck), retail salesperson, cashier, food and beverage worker, office clerk.

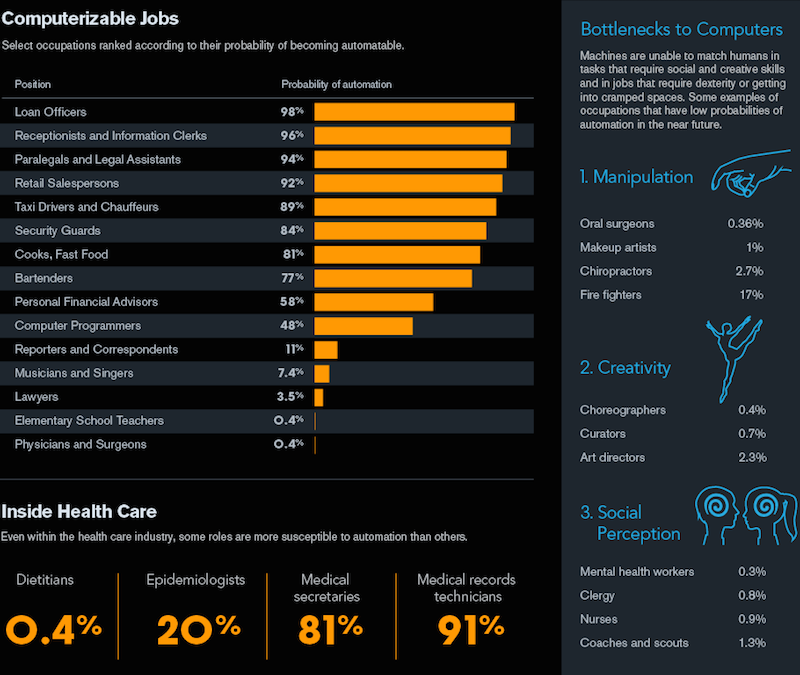

Below, Bloomberg’s chart of jobs likely to be done by smart machines before too long.

Thompson’s solution is a big government one, namely a universal basic income. If there is a conservative fix, I haven’t heard it. In fact, the right-wing press and politicians have been ignoring the problem. One notable exception is Sen Jeff Sessions who connected automation with a reduced need for immigrants in an op-ed. None of the Presidential candidates of either party have mentioned the automated future, and that is worrisome.

Thompson mentioned the Oxford University study in passing. That was the 2013 report estimating 47 percent of US jobs were susceptible to automation within 20 years. Millions of American jobs are going the way of the buggy whip, so the nation certainly does not need to import millions of immigrant workers to do work that no longer exists. Let’s just avoid that stupid foreseeable mistake.

FAREED ZAKARIA GPS, CNN, August 23, 2015ZAKARIA: The great economist John Maynard Canes [sic] looked at his crystal ball in 1930 and imaged life 100 years later, in 2030. In a piece entitled “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” he envisioned those descendants of his working only 15 hours a week yet producing enough to live happy and fulfilled life with lots of leisure time.

It’s not 2030 yet but a not-so surprising survey by Gallup last year found that only 8 percent of American full-time workers work less than 40 hours a week, 42 percent work the standard 40 hours, and the other 50 percent, well, they work more than 40 hours a week. But are we at a turning point? Will the huge advances in robotics and artificial intelligence strip away more and more jobs from us humans until we are all working about 15 hours a week? And will that be the fulfillment of Canes’ dream or a nightmare of part-time work, low wages and job insecurity?

Derek Thompson has written a great long read for “The Atlantic” called “A World Without Work” about all this and much more.

Welcome, Derek.

THOMPSON: Thank you. Good to be here.

ZAKARIA: You start with Youngstown, Ohio. Explain why. What’s the story there?

THOMPSON: Youngstown, Ohio, in many ways, was the American dream of the 20th century. It had one of the highest typical incomes for young people, it had perhaps the highest rate of home ownership of any city in the U.S. in the middle of the 20th century. But then something happened in the next 20 years. The steel industry started to collapse for a variety of reasons, globalization and technology.

And in September 1977 an enormous steel mill in Youngstown essentially said we’re done, we’re shutting down. So while the rest of America thinks about the end of work as a futuristic concept Youngstown very much has experienced something very much like the end of work. So I went there to see how have they dealt with it in the decade since. And in many —

ZAKARIA: What did you find?

THOMPSON: In many ways, you know, people are — people are still leaving Youngstown. The effects are still rippling through this community. And what I found is that as people have found fewer opportunities of full-time work in the labor force that exists in Youngstown, they’ve found ways to make do. They’ve cobbled together jobs. There are people there who work as T-shirt designers and bartenders and they do urban agriculture and they fix cars and they write poetry.

And so what’s interesting is that, you know, when most people go to, say, a social gathering, the question is, what do you do? What’s that one thing you do? In Youngstown the question isn’t what do you do, what’s the one thing, it’s what can you do. One of the four things, the five things. So what struck me as fascinating about Youngstown is that if this is a glimpse of the future and the pillar of work that was steel there collapses for more of us, will it be replaced with despondency or will it be replaced with something like resiliency.

ZAKARIA: Now the traditional answer to your question about — to your puzzle about Youngstown would have been, yes, Derek, of course they’re leaving and of course those people who stay behind for some reason sticky or, you know, having difficult lives but guess what, you’re not looking at all those places in the southwest that are growing. There are new industries, there are new communities that are thriving and bubbling.

And that in the aggregate what has happened is new industries, new jobs have come along. But you say in the article that this time it may be different.

THOMPSON: There is no question that the grand narrative of technological change in economics is creative destruction with an emphasis on the adjective creative. We are doing jobs that we could not have done 200 years ago when we were an agrarian economy. Even 60 years ago, we were a manufacturing economy. Now we’re a services economy and what comes next.

But you look at sort of the fleet of automated technologies, of software that exists right now, and it’s rather frightening to me to think about how many jobs can be replaced by technologies that we understand to be right on the horizon. Two examples. The first example is driving. Driving is the most common occupation among American men.

ZAKARIA: You said that in the article. I was surprised by that. You mean, really cab drivers, limo drivers?

THOMPSON: Cab and truck drivers. As you take both those categories, you put them together, that is the single biggest thing that American men do. Now we’re already talking right now about Google designing self-driving cars, about Uber taking all of these scientists from Carnegie Mellon to have their own self-driving cars. This is a serious threat to employment in the U.S. if you begin to have self- driving automobiles.

Then you look at the four most common occupations in the U.S. economy. They are, in order, retail salesperson, cashier, food and beverage worker, office clerk. All of these jobs, according to Oxford university, which has looked at the automatability (ph) of all of these occupations in the U.S., seem to them to be extremely automatable either with technology we have right — better checkout kiosks, better checkout machines — or with technology that’s right on the horizon.

So I do think that this time is different. We are not back in 1920 or 1950. This is a new horizon.

ZAKARIA: So then that comes back to the Youngstown model, which is this kind of collection of part-time jobs and some leisure, poetry and such. Is that good? Is that progress?

THOMPSON: This is perhaps the essential question of the piece. Do we need to work to be happy? And this is a very difficult question to answer because right now everybody — most people need to work in order to have money, and they need money in order to buy the essentials of life. So it’s sort of like asking like, would we be less anxious without gravity? It’s very difficult to sort of find a control group for this question.

There is something about busyness, something about losing yourself in the flow of a job and the flow of a good challenge that does really feed the human soul. And so when I look at this piece, when I look at this future, I think leisure is a possibility. You could have a lot of people who just don’t do anything. But I don’t see that as even scraping utopia.

I hope that we can find ways to push people into jobs that are more creative, that allow for more of this flow, less of this anxiety, more of these positive feelings, and we can use technological change to allow people to perhaps find their passions.

ZAKARIA: Do you — do you end up hopeful or worried?

THOMPSON: I am hopeful about people and extremely worried about government. I don’t think that the government that we have today can enact a law like a universe basic income, a kind of Social Security for everyone, a government check for everybody, which I think is absolutely essential for people to use technological change, to use technological unemployment to push toward a better future.

I don’t see that in the capacity of 2015s U.S. federal government. At the same time I think that people themselves are resilient and people want to be happy. And you can imagine all sorts of community solutions to this problem, even technological solutions to the problem of technological unemployment by which people can come together and do things that we can imagine right now which would make them feel more fulfilled.

ZAKARIA: Terrific stuff. Thank you, Derek.