That’s the thought that occurred to me after finishing Robert Putnam’s book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, published a few weeks ago. ![our-kids-9781476769899_hr[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/our-kids-9781476769899_hr1-199x300.jpg)

The “American Dream” in Putnam’s subtitle is the dream of universal opportunity through social mobility. The song he sings is familiar now, if you pay any attention at all to academic-strength social commentary:

Charles Murray plowed the same field three years ago with Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010. There is in fact a YouTube video of Murray and Putnam sitting together and talking about Coming Apart at a discussion staged by the Aspen Institute in March 2014.

For symmetry, YouTube also has a video of an American Enterprise Institute discussion from last month where Murray, Putnam, and black sociologist William Julius Wilson talk about Putnam’s book Our Kids, the book I’ve just been reading.

The American dream in crisis? A discussion with Robert Putnam and Charles Murray, Streamed live on Jun 22, 2015

Our Kids is mostly descriptive. The first 226 pages tell us about the lives of some representative prole and gentry Americans. Then comes that 45-page closing chapter of pre-scriptions, title “What Is to be Done?”

There follows a litany of liberal nostrums that would have Barack Obama clapping along enthusiastically. Give the proles more money through tax credits and welfare; reduce incarceration and enhance rehabilitation; expand preschool education; put good teachers in bad schools; “move poor families to better neighborhoods,” …

Putnam is an odd bird: a professor of Political Science at Harvard who, as a hardcore Midwestern liberal ideologue, instinctively practices crimestop when his honestly-intended, methodologically-sound, professionally-conducted researches uncover truths that are unwelcome to him.

The psychic deformations thus induced were most clearly on display in Putnam’s 2006 paper on diversity, with which I had some sport in We Are Doomed:

Putnam is, in short, a bigfoot scholar who can dress, cook, and serve a fine table of research in the human sciences … which he then, for reasons ideological, finds himself unable to digest.The paper is titled “E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century,” and can easily be found on the internet …

That paper has a very curious structure. After a brief (2 pages) introduction, there are three main sections, headed as follows:

I’ve had some mild amusement here at my desk trying to think up imaginary research papers similarly structured. One for publication in a health journal, perhaps, with three sections titled:

- The Prospects and Benefits of Immigration and Ethnic Diversity (three pages)

- Immigration and Diversity Foster Social Isolation (nineteen pages)

- Becoming Comfortable with Diversity (seven pages)

Social science research in our universities cries out for a modern Jonathan Swift to lampoon its absurdities. [We Are Doomed, p.16.]

- Health benefits of drinking green tea

- Green tea causes intestinal cancer

- Making the switch to green tea

For a guy prominent in a field that has the word “science” in its title, he has a weirdly blithe approach to matters of cause and effect. This latest book actually includes the following sentence:

Figure 2.7 shows the explosion of incarceration rates in the years after 1980, despite a decline in violent crime during that same period. [Our Kids, p.76.]

He relies heavily on the post hoc fallacy, and on studies that employ it:

Waldfogel has shown that (even after controlling for many other factors) dining is a powerful predictor of how children will fare as they develop. “Youths who ate dinner with their parents at least five times a week,” she writes, “did better across a range of outcomes …”The reader who has not cultivated crimestop might reflect: “Oh, so parents disposed to structure and order in their lives transmit that disposition to their kids? Doesn’t Occam’s Razor suggest that the mechanism of transmission is likely biological? Don’t red-haired parents transmit red hair to their kids?”

That reader will never hold a chair in the human sciences at Harvard.

As in the 2006 diversity paper, Putnam is driven at last to prescribing a change of heart. At the very end of that final chapter headed “What is to be done?” he frowns at Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1841 essay “Self-Reliance.”

Emerson:

Do not tell me, as a good man did to-day, of my obligation to put all poor men in good situations. Are they my poor? I tell thee, thou foolish philanthropist, that I grudge the dollar, the dime, the cent, I give to such men as do not belong to me and to whom I do not belong.Putnam:

The better part of two centuries later, speaking of the recent arrival of unaccompanied immigrant kids, Jay Ash, city manager and native of the gritty, working-class Boston suburb of Chelsea, drew on a more generous, communitarian tradition: “If our kids are in trouble—my kids, our kids, anyone’s kids—we all have a responsibility to look after them.”So apparently the “our kids” of Putnam’s title includes the kids of Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, and (presumably) any other nation whose adult citizens can find a way to impose their offspring on us by violating our laws. Good to know.In today’s America, not only is Ash right, but even those among us who think like Emerson should acknowledge our responsibility to these children. For America’s poor kids do belong to us and we to them. They are our kids. [Our Kids, p.261.]

*

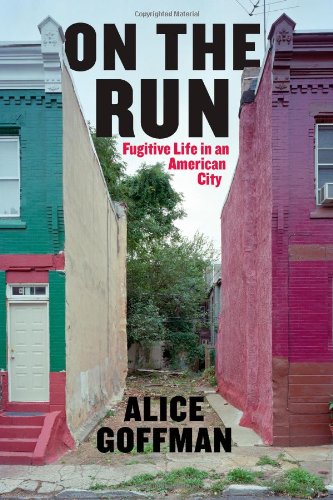

The prescriptive poverty of the social sciences was also on display in the previous social-science bestseller I read, Alice Goffman’s 2014 book On the Run: Fugitive Life In An American City.Goffman, a young white woman, spent six years living among black proles in a Philadelphia slum for which she invented the cover name “6th Street.” Again, the main part of her book—pages 9 to 194—is simply descriptive. It is in fact really just journalism, with very few numbers and not a single table, graph, or chart.

I should add that On the Run is rather good journalism, quite gripping to read. The chaotic lives of black proles are vividly described. The young men dodge police, plan for their next drug test, and engage in concurrent sexual relationships. The young women raise kids, hold minimum-wage jobs, and fight over the men.

Then comes that prescriptive chapter. I can’t improve here on Amy Wax’s critique of the book in the June 2015 issue of Commentary. From which:

So what is to be done about 6th Street? Taking refuge in her descriptive mission as a “fly on the wall,” Goffman avoids any systematic recommendations. But that doesn’t stop her from treating us to a penultimate chapter of jargon-ridden, stream-of-consciousness J’accuse. According to Goffman, our society has erected an oppressive police state that targets black men for depredations akin to those visited on “persecuted groups throughout history—from Jews in Europe to undocumented immigrants in the United States to people anywhere living under oppressive, authoritarian, or totalitarian regimes.” In collapsing critical and painfully obvious distinctions, this passage stands out as an especially egregious exercise in flawed moral equivalence, steeped in the rhetoric of structural forces and social conditions. Everyone is a victim here. It’s not that the police are “bad people” but rather that they have been placed in “an impossible situation” by the usual disembodied suspects: poverty, unemployment, drugs, violence, and the “social problems of able-bodied young men in a jobless ghetto.” This laundry list, endlessly repeated by social scientists everywhere, sidesteps critical chicken-and-egg issues. Goffman never tells us how to tackle unemployment when “able-bodied” men lack rudimentary skills and desirable habits. One can only hope that Goffman’s next ethnographic project will have her examining a small business struggling to cope with a staff of poorly socialized, unruly, functionally illiterate, profane, defiant ex-cons. [Negatively Sixth Street by Amy Wax; Commentary, June 2015.]

*

For the reflective general reader, the social-science classic of the past few years remains Charles Murray’s Coming Apart.Murray lays out the prole-gentry divergence with exceptional clarity and great masses of supporting data. He is wise enough to know that apart from some scattered insights in particular areas—“broken-windows” policing, for instance—the social sciences are at present merely descriptive, like biology before Darwin.

Yet even Murray can’t resist that closing prescriptive flourish. His prescription in Coming Apart is, like Putnam’s in Our Kids, for a change of heart; but instead of us all opening our minds—and our nation’s borders—to limitless moral universalism, Murray more modestly hopes that our gentry will set a good example to the lower orders.

A large part of the problem consists of nothing more complicated than our unwillingness to say out loud what we believe. A great many people, especially in the new upper class, just need to start preaching what they practice.That makes for a good upbeat ending. Murray is, however, too respectful of data to nurse false hopes, and seems never to have mastered crimestop.And so I am hoping for a civic Great Awakening among the new upper class … [Coming Apart, p. 305.]

In last month’s AEI event discussing Putnam’s book Murray drew the audience’s attention to the humongous meta-study on the heritability of human traits published in Nature this spring.

With that as his foundation, and after some collegially respectful words about Our Kids as a work of descriptive sociology, Murray mercilessly pooh-poohed Putnam’s prescriptions—and his own, too!

Bob [Putnam] has already referred to my take-away from all this with the ways in which we really need a civic Great Awakening. However, I’ve got to say that the fact is, civic Great Awakenings have about as much chance of transforming what’s going on as a full implementation of Bob’s “purple” [i.e. neither “red” nor “blue” politically] programs does.The parsimonious way to extrapolate [from] the trends that Bob describes so beautifully in the book is to predict an America permanently segregated into social classes that no longer share the common bonds that once made this country so exceptional; and the destruction of the national civic culture that Bob and I both cherish. I hope for a better outcome: I do not expect it.[43 minutes, 24 seconds in the video.]

*

Their descriptive virtues aside, Putnam’s Our Kids and Goffman’s On the Run are qualitatively inferior to what can now be found on the internet.There is now a good nucleus of human-science bloggers providing day-to-day commentary on the human sciences. Some of them, like Bruce Charlton and Greg Cochran, are accredited academics; others, like JayMan and HBD Chick, are thoughtful nonspecialists.

Checking in once or twice a week on these sites, and following their links to news stories and academic papers, is a better way to keep informed on current understandings in the human sciences than diligently reading bestsellers steeped in the left-liberal Narrative.

There is of course a lot of speculation mixed in with the reportage; but the wilder kind doesn’t survive the to-and-fro of the comment threads, and speculation is anyway a key early stage in hypothesis formation.

If the study of human nature interests you, spend a couple of hours reading JayMan’s recent rumination on empathy and universalism, or James Thompson’s on African intelligence. Chase down the links and watch the comment-thread jousting.

Then ask yourself whether you any longer want to engage with the vast, gaseous, arrogant blob of left-liberal social commentary when it is anything other than flatly descriptive.

John Derbyshire [email him] writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him. ) He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. His most recent book, published by VDARE.com com is FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT (also available in Kindle).His writings are archived at JohnDerbyshire.com.

Readers who wish to donate (tax deductible) funds specifically earmarked for John Derbyshire's writings at VDARE.com can do so here.