Naturally, nobody mentioned that increased use of smart machines means America doesn’t need to import millions of immigrant workers to replace retiring boomers.

Naturally, nobody mentioned that increased use of smart machines means America doesn’t need to import millions of immigrant workers to replace retiring boomers.

The WSJ discussed the industrial trend toward more machines and fewer human workers.

New Manufacturing Trend: More U.S.-Based, More Robots, Less Jobs, Wall Street Journal, May 21, 2014A shortage of low-cost labor in Asia is leading manufacturers to speed up the adoption of technology to automate their factories and to consider moving some operations back to the U.S. These U.S.-based digitally-equipped factories could increase productivity by using Big Data, software, sensors, controllers and robotics.

There are many advantages to this approach, said experts on a panel, Tuesday evening, at an event hosted by General Electric Co. in San Francisco. Goods will no longer need to be shipped around the world, lessening the impact to the environment. Fewer workers will be mistreated in far-flung factories and new U.S. businesses will emerge, they said. Still, some panelists acknowledged that as this automation spreads it could mean rising unemployment globally.

Today, there are fewer young workers available to work in factories in China. Not only has the population of young people declined but they’re increasingly going to college rather than working on assembly lines, according to Bloomberg Businessweek’s Christina Larson. From 2008 to 2010, the number of 18-year-olds in China dropped by one-fifth, she notes.

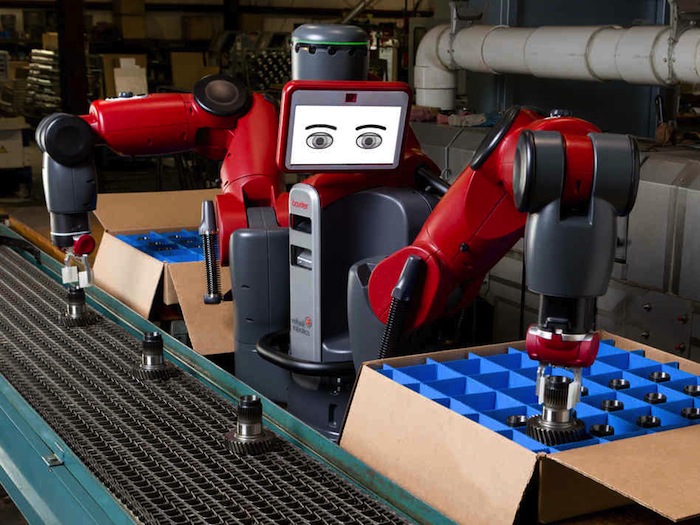

“We’re seeing a 30% drop in 19-year-olds in China for the next 10 years,” said Rodney Brooks, founder of Rethink Robotics, which makes humanoid robots that can work in factories alongside humans. Mr. Brooks also co-founded iRobot Corp., maker of the Roomba vacuum cleaning robot. Some of the factory jobs have moved to other countries in Asia such as Vietnam and Thailand but companies are running out of places with low-cost labor, he said.

“It seems to me the only thing we can do is to use technology to increase productivity of people in the U.S. and Europe,” said Mr. Brooks.

There’s still a great deal of factory work that can be automated. “Roughly 10% of the world’s workforce is employed sewing garments,” said Saul Griffith, co-founder and CEO of Otherlab, a research and development company working on computational manufacturing and design tools. The creation of airline blankets is one of the few sewing tasks that have been completely automated because the blankets are square, he said.

Even so, Mr. Griffith acknowledges the impact that automation has on jobs and workers. “We’re already seeing the widening gap between the rich and poor which is a result of having the capital to invest in automation,” he said.

Technology is hurting some groups disproportionately more than others, according to Erik Brynjolfsson, director of the MIT Center for Digital Business at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Those most at risk are unskilled and middle skilled workers. That applies not just to factory workers, but many so-called knowledge workers as well. “Routine information processing is in the bullseye of automation,” he said during an interview. “I think that’s only going to accelerate.”

He says society needs to encourage more education in areas where humans are still better than machines — such as leadership, motivating other people, and nurturing. People with these skills are “less likely to see their tasks automated,” he said.