|

| Poor blacks more likely to stay poor, black

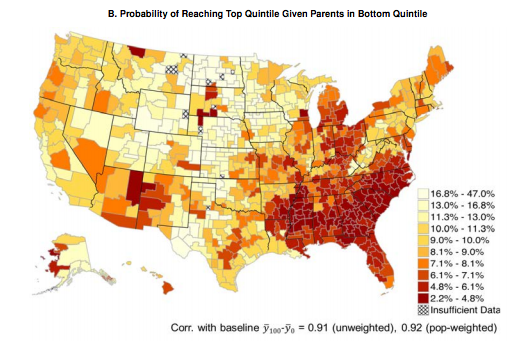

In other words, this is basically a map of blacks and huge Indian reservations |

Why Is the American Dream Dead in the South?Upward mobility has stayed the same the past 50 years despite skyrocketing inequality. But it's lower in the South (and Ohio) than anywhere else in the U.S.—or the rest of the developed world.

MATTHEW O'BRIEN

JAN 26 2014, 9:00 AM ET

The top 1 percent aren't killing the American Dream. Something else is—if you live in the wrong place.

Here's what we know. The rich are getting richer, but according to a blockbuster new study that hasn't made it harder for the poor to become rich. The good news is that people at the bottom are just as likely to move up the income ladder today as they were 50 years ago. But the bad news is that people at the bottom are just as likely to move up the income ladder today as they were 50 years ago.

We like to tell ourselves that America is the land of opportunity, but the reality doesn't match the rhetoric—and hasn't for awhile. We actually have less social mobility than countries like Denmark. And that's more of a problem the more inequality there is. Think about it like this: Moving up matters more when there's a bigger gap between the rich and poor. So even though mobility hasn't gotten worse lately, it has worse consequences today because inequality is worse.

But it's a little deceiving to talk about "our" mobility rate. There isn't one or two or even three Americas. There are hundreds. The research team of Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Herndon, Patrick Kline, and Emmanuel Saez looked at each "commuting zone" (CZ) within the U.S., and found that the American Dream is still alive in some parts of the country. Kids born into the bottom 20 percent of households, for example, have a 12.9 percent chance of reaching the top 20 percent if they live in San Jose. That's about as high as it is in the highest mobility countries. But kids born in Charlotte only have a 4.4 percent chance of moving from the bottom to the top 20 percent. That's worse than any developed country we have numbers for.

And yet all sorts of people are disagreeing with Professor Chetty and pouring into Charlotte. From Wikipedia on the municipality of Charlotte:

2000 population: 540,828

2012 population: 775,203

Chetty's study fails simple reality checks. For example, he finds Charlotte to have the worst prospects of any metropolitan zone in the country. Yet, Charlotte has been growing rapidly because hundreds of thousands of people don't think Prof. Chetty is right.

And much of that population growth stems from African-Americans moving from the North down South. From the New York Times:

For New Life, Blacks in City Head to SouthBy DAN BILEFSKY

Published: June 21, 2011

... The economic downturn has propelled a striking demographic shift: black New Yorkers, including many who are young and college educated, are heading south.

About 17 percent of the African-Americans who moved to the South from other states in the past decade came from New York, far more than from any other state, according to census data. Of the 44,474 who left New York State in 2009, more than half, or 22,508, went to the South, according to a study conducted by the sociology department of Queens College for The New York Times.

The movement is not limited to New York. The percentage of blacks leaving big cities in the East and in the Midwest and heading to the South is now at the highest levels in decades, demographers say.

... New York is increasingly unaffordable, and blacks see more opportunities in the South.

The South now represents the potential for achievement for black New Yorkers in a way it had not before, Professor Crew said. At the same time, unionized civil service jobs that once drew thousands of blacks to the city are becoming more scarce.

... But Ms. Brown says New York is now less inviting. She plans to join her 26-year-old son, Rashid, who moved to Atlanta from Queens last year after he graduated with a degree in criminology but could not find a job in New York.In Atlanta, he became a deputy sheriff within weeks. She is hoping to open a restaurant.

“In the South, I can buy a big house with a garden compared with the shoe box my retirement savings will buy me in New York,” she said.

A massive problem with Chetty's map, as I pointed out in the NYT last summer is that the cost of living varies so much across the country. San Jose has very high land costs and very high wages. Charlotte has modest land costs and modest wages. They are both fairly successful places, but Chetty's methodology puts them at opposite ends of the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the country because he failed to consider the standard of living.

The other element is that the Bad Parts of the map largely denotes two things: Where the blacks are, and big Indian reservations.

In contrast, note how West Virginia jumps out as a Beacon of Hope. Why? Because it's economy and education are so top notch? Nope. They're not. But West Virginia is very white, and whites regress toward a higher mean over the generations.

Let's look at Wikipedia for demographics in the 2010 Census. These numbers will be only for within the municipal boundaries, but they will give us a clue about the differences between who is in the bottom 20% in San Jose, CA versus who is in the bottom 20% in Charlotte, NC.

Percent African-American in 2010:

San Jose: 0.9%

Charlotte: 35.0%

Back to The Atlantic:

You can see what my colleague Derek Thompson calls the geography of the American Dream in the map below. It shows where kids have the best and worst chances of moving up from the bottom to the top quintile—and that the South looks more like a banana republic. (Note: darker colors mean there is less mobility, and lighter colors mean that there's more).So what makes northern California different from North Carolina? Well, we don't know for sure, but we do know what doesn't. The researchers found that local tax and spending decisions explain some, but not too much, of this regional mobility gap. Neither does local school quality, at least judged by class size. Local area colleges and tuition were also non-factors. And so were local labor markets, including their share of manufacturing jobs and those facing cheap, foreign competition. But here's what we know does matter. Just how much isn't clear.

1. Race. The researchers found that the larger the black population, the lower the upward mobility. But this isn't actually a black-white issue.

Actually, the overall shape of the map is a black-white (or black-everybody else issue). Black children in the bottom 20% regress toward the black mean (median income of $33k), while white children in the bottom 20% regress toward the white mean (median income of $57k). In other words, poor blacks tend to stay poor, black.

It's a rich-poor one. Low-income whites who live in areas with more black people also have a harder time moving up the income ladder. In other words, it's something about the places that black people live that hurts mobility.

In other words, the children of whites who can't afford to insulate, insulate, insulate them from poor blacks have poorer prospects in life.

2. Segregation.

Segregation is largely a function of the number and class of blacks. There's no segregation in the city of San Jose because less than 1% of the population is black. The newer, faster growing parts of the country have less segregation than the old cities, but see Sprawl below for rationalization.

Something like the poor being isolated—isolated from good jobs and good schools. See, the more black people a place has, the more divided it tends to be along racial and economic lines. The more divided it is, the more sprawl there is. And the more sprawl there is, the less higher-income people are willing to invest in things like public transit.

Oh, boy, "sprawl" as the problem of the black poor ... That's why poor blacks are doing so well in Baltimore. In contrast, San Jose has zero sprawl.

That leaves the poor in the ghetto, with no way out for their American Dreams. They're stuck with bad schools, bad jobs, and bad commutes if they do manage to find better work. So it should be no surprise that the researchers found that racial segregation, income segregation, and sprawl are all strongly negatively correlated with upward mobility. But what might surprise is that it doesn't matter whether the rich cut themselves off from everybody else. What matters is whether the middle class cut themselves off from the poor.

Huh? Anyway, Charlotte, which is the bete noire of this article had a famous, much praised countywide school busing program that lasted for decades.

3. Social Capital. Living around the middle class doesn't just bring better jobs and schools (which help, but probably aren't enough). It brings better institutions too. Things like religious groups, civic groups, and any other kind of group that keeps people from bowling alone. All of these are strongly correlated with more mobility—which is why Utah, with its vast Mormon safety net and services, is one of the best places to be born poor.4. Inequality. The 1 percent are different from you and me—they have so much more money that they live in a different world. It's a world of $40,000 a year preschool, "nanny consultants," and an endless supply of private tutors. It keeps the children of the super-rich from falling too far, but it doesn't keep the poor from rising (at least into the top quintile). There just wasn't any correlation between the rise and rise of the 1 percent and upward mobility. In other words, it doesn't hurt your chances of making it into the top 80 to 99 percent if the super-rich get even richer.

As I pointed out in 2010, the rich don't take all that much land in America, they don't get all the hospital beds, and their kids don't wreck the public schools for your kids. What the rich do, however, is control the media, so policies that would economically benefit the average person are demonized as unthinkable.

But inequality does matter within the bottom 99 percent. The bigger the gap between the poor and the merely rich (as opposed to the super-rich), the less mobility there is. It makes intuitive sense: it's easier to jump from the bottom near the top if you don't have to jump as far. The top 1 percent are just so high now that it doesn't matter how much higher they go; almost nobody can reach them.5. Family Structure. Forget race, forget jobs, forget schools, forget churches, forget neighborhoods, and forget the top 1—or maybe 10—percent. Nothing matters more for moving up than who raises you. Or, in econospeak, nothing correlates with upward mobility more than the number of single parents, divorcees, and married couples. The cliché is true: Kids do best in stable, two-parent homes. ...

I'll insert the relevant demographic figures in the next paragraph:

The American Dream is alive in Denmark and Finland and Sweden. And in San Jose (0.9% black in city) and Salt Lake City (2.7% black in city) and Pittsburgh (has a ghetto but the surrounding commuting zone is one of the whitest in the country). But it's dead in Atlanta (city is 54% black) and Raleigh (29% black) and Charlotte (35% black). And in Indianapolis (28% black) and Detroit (don't ask) and Jacksonville (31% black). Fixing that isn't just about redistribution. It's about building denser cities, so the poor aren't so segregated.

Because black people have done so well in high density cities like Chicago, Milwaukee, Baltimore, and the Bronx.

This is just SWPL bullying. SWPLs want to live in denser cities and they want to squeeze poor blacks out of their cities, so they just make up rationalizations about how they are pushing through density to benefit poor black people.